My Experience at a Small Town Newspaper

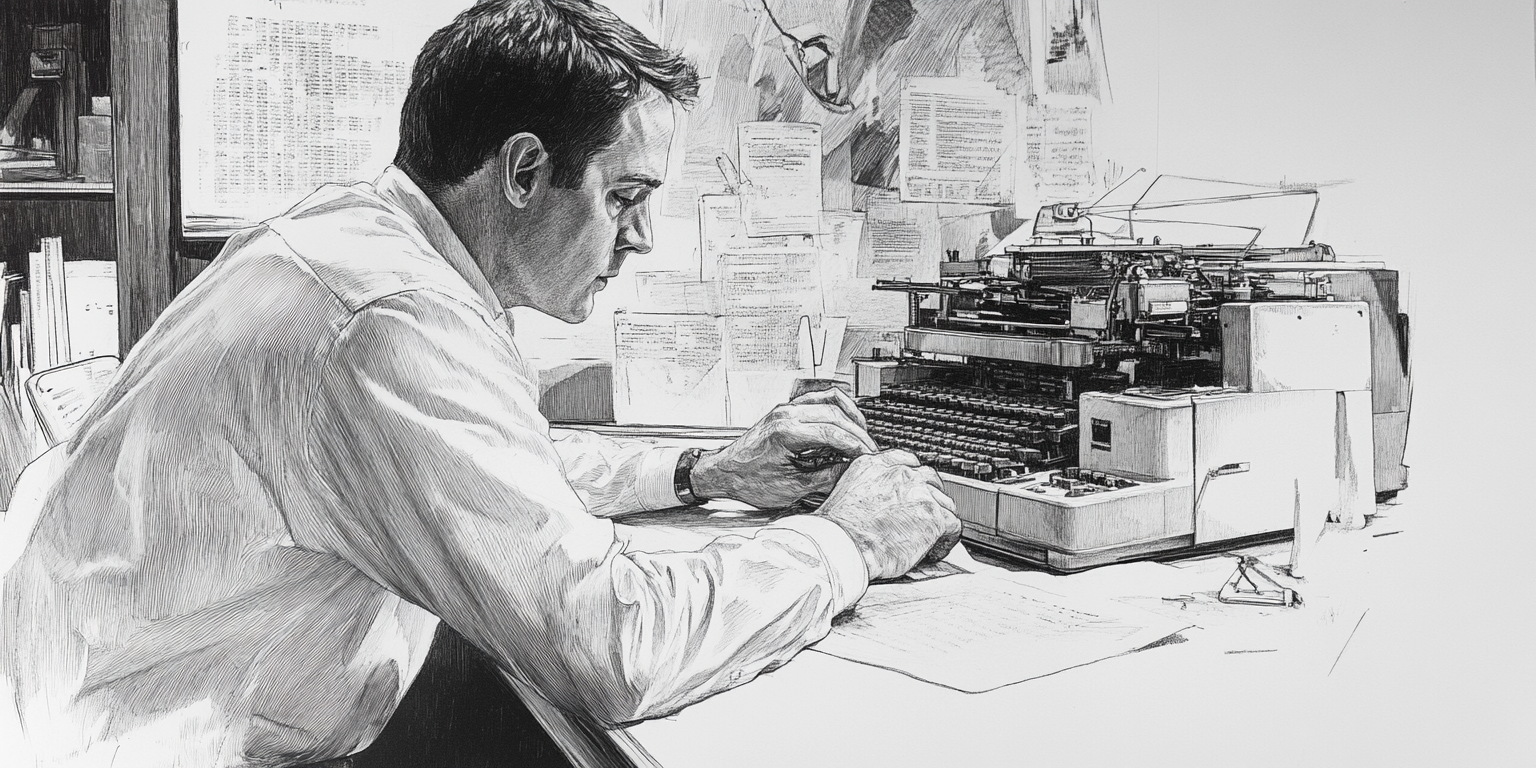

In 1987, at just 19 years old, I joined the staff of the Fountain Hills Times in Arizona as a phototypesetter operator. This position placed me at the heart of community journalism during a pivotal moment in publishing history—the final years before digital technology would transform the industry forever.

My primary responsibility involved operating a sophisticated phototypesetting machine, where I would type articles on a specialized keyboard terminal. As I typed each line and pressed enter, the machine would expose light-sensitive film one line at a time. Precision was paramount; a single typing error meant retyping the entire line and developing a new film strip to replace the flawed one.

I still vividly remember how the editor-in-chief’s wife would monitor the typesetting process with eagle eyes. Whenever I made a typing error—which was inevitable given the volume of text—she would march over to my station with an exasperated sigh that could be heard across the newsroom. “Not AGAIN!” she would exclaim, as though each typo personally offended her. “Now we have to develop a WHOLE NEW LINE!” Her dramatic emphasis on the wasted time and materials made each mistake feel like a small catastrophe. Looking back, it’s amusing how a single misplaced letter could cause such consternation in the pre-digital era, when today an error can be fixed with a simple keystroke.

After completing a story, I would cut the film and deliver it to the developing room. Once processed, these strips of text emerged ready for the next stage of production. I would then assist in the mechanical paste-up process, carefully positioning these text strips onto large layout boards that matched the exact dimensions of the newspaper pages.

These completed paste-up boards represented the physical blueprint of each edition, which would then be photographed to create negatives for the printing plates. My responsibilities extended beyond the newsroom as well—I would collect the freshly printed newspapers from the printer and distribute them to key vendors throughout Fountain Hills.

Working at this small community newspaper gave me firsthand experience with a production method that had evolved over decades but was on the verge of extinction. The phototypesetting technology I operated bridged the gap between traditional hot metal typesetting and the desktop publishing revolution that would soon follow.

The Fountain Hills Times served as a vital communication hub for the community, chronicling local events, government decisions, and community milestones that larger publications wouldn’t cover. My role in bringing these stories to the community offered a unique window into both journalism and the technological transition that would soon revolutionize the industry.

This experience—capturing the end of an era in publishing technology while serving the information needs of a growing Arizona community—provides me with a distinctive perspective on the evolution of media and communication that few people today have experienced firsthand.